Image: Blog hero Plant Plate 09 boys dig in

Image: Blog hero Plant Plate 09 boys dig in

Rural “neighborhood effects” give kids a leg up for future job earning

by Blandin Foundation Posted in Vibrant Rural

Last year, Stanford economist Raj Chetty and other researchers found that “children growing up in poor families in three out of four rural counties have higher incomes than the national average at age 26 simply as a result of spending time in these communities.”

Star Tribune’s Adam Belz wrote a three-part series on the research in December 2016, highlighting examples from Minnesota. The Daily Yonder recently highlighted the research. It’s important to keep this research in front of us — especially when working on rural youth initiatives (like SPARK in the Itasca area).

Here are a few key takeaways:

The study finds a number of factors that benefit children. Communities that are less racially segregated, that don’t have wide disparities in income, that have good schools and have a strong civic life produce grown-ups who earn more than people who grow up in places without those qualities.

—————————————————

Chetty, Hendren and the other researchers in this project have attempted to isolate the community factors that affect the income of those who grow up in these places. The connections are hard to make, and the researchers are still teasing out the data.

But they have already identified some factors:

Income inequality. Places with a great amount of income inequality have worse outcomes for poor children.

Segregated places reduce future incomes for both white and black children in poor families.

Places with high “social capital” — low crime rates, lots of religious and civic organization, high levels of trust — are good for poor children.

Education matters. The researchers found that places with low test scores and higher dropout rates were worse for poor children. (Children from well-off families seem to do fine regardless of school quality.) Chetty found that measures of education “input” — class size or spending per student — seemed to have less bearing.

The impact of all these community effects is greater for boys than for girls.

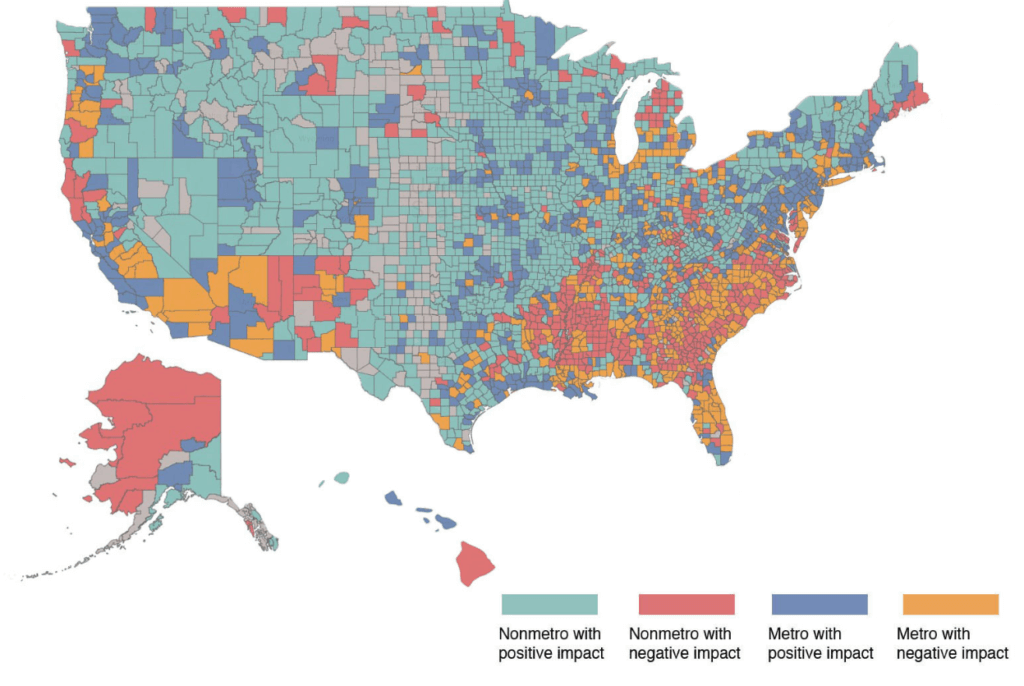

The map shows that areas with a higher percentage of black and Native American residents have less upward mobility. The researchers find that this is a combination of community effects — these places may have more segregation and poorer schools — and discrimination.